I don’t want to pin this all on fear. I don’t want to see (or portray) fear as an all-enveloping miasma that swaddles voters in a cartoon fog, stripping away any possibility of clarity or agency. But fear is certainly a factor. (So are: white supremacy, misogyny, homophobia, climate denial, austerity, growing debt, precarity, and quotidian self-interest; all bolstered, bounded and bundled up with—ta da!—fear.)

So, today, as I try to metabolize the results of last night’s election, as my mind ricochets about the room, as I attempt to lower my shoulders from their now-alarmingly raised position, I find myself reflecting on FEAR. Specifically, I find myself returning to a passage from Eula Biss’s book On Immunity:

“What has been done to us seems to be, among other things, that we have been made fearful. What will we do with our fear? This strikes me as a central question of both citizenship and motherhood.”

I won’t get into the intricacies of Biss’s stunning and meandering exploration (I recommend you read it yourself) but what stays with me today is Biss’s call to examine the political nature of fear. How does fear cleave and shrink our collective imaginations? In the face of monstrous scaremongering, how do we countervail? Can we (those of relative power and privilege) avoid the urge to withdraw? Can we fend off the urge to indulge in our own fear impulses, e.g. fortressing ourselves and our kin from the threats and horror of the world—a survivalist approach that can be marshaled to rationalize THE MOST privileged and anti-communal actions? Can we heed the need for communal care and responsibility—cultivating a more generative and generous survivalism? How on earth (in these unevenly threatening times) do we frame our interactions with the world?

“What will we do with our fear?”

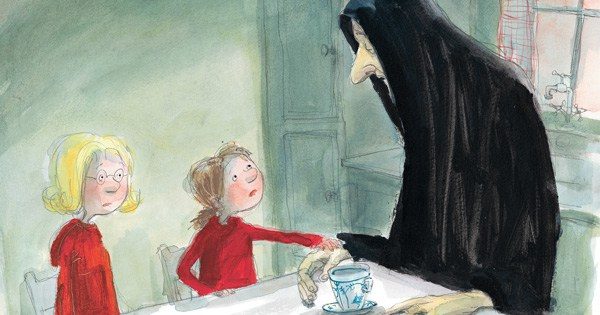

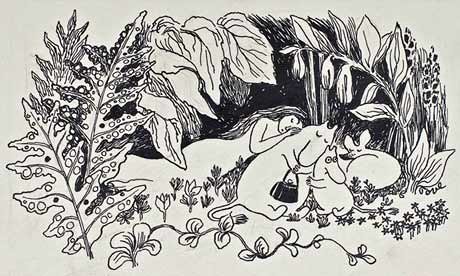

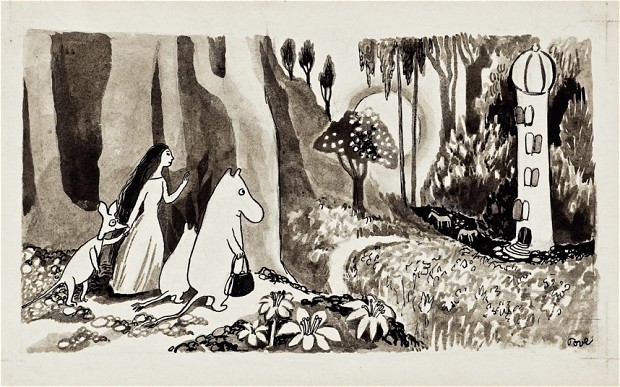

I don’t have the answer. But I do have a good picture book. It’s called The Moomins and The Great Flood. It was originally published in Finland in 1945 by Tove Jansson and I think it offers one possible scenario—or, even, a revolutionary retort to fear. Briefly: the Moomins are refugees from human civilization and their father Moominpappa has disappeared. Loaded with fear and worry, Moominmamma and Moomintroll set off to look for him.

The family bond that unites the Moomin pair is intensely loving, but it is also open-ended. Disparate creatures, estranged from the world and brought together by the devastation of a great flood, are welcomed into the fold. Sniff joins the family. Tulippa finds a home in a lighthouse, guiding other lost creatures to safety. The Hemulens and Hattifatteners are also represented as kindred spirits in the Moomin world.

Given the tumultuous setting, I was not surprised to learn that the idea for the Moomins came to Tove Jansson during World War II. “It was the winter of war, in 1939,” she writes in the books’ introduction, “my work stood still; it felt completely pointless to try to create pictures. Perhaps it was understandable that I suddenly felt an urge to write down something that was to begin with ‘Once upon a time’. What followed had to be a fairytale – that was inevitable – but I excused myself by avoiding princes, princesses and small children.”

In other words, the Moomins—creatures forced to flee their homes—were born of Jansson’s anxiety and distress at the state of the world (a world, not incidentally, in the grip of racial hatred and far-right populism.) What feels significant to me today is how she found solace and hope in imagining a multifarious community. What feels emboldening is the idea that art can be a way forward through despair. The Moomins and the Great Flood may be a story about a terrible disaster but it is also a story about the formation of an extended family where misfits and orphans are always welcome, where “making kin and making kind,” in the sense Donna Haraway has proposed, can “stretch the imagination and can change the story.”

In a climate of fear and grief, when a sense of safety feels most precarious, Tove Jansson shows that there are moments of refuge to be found in generosity, in the willingness to make homes and open them to those who need them—i.e. those most targeted, those most vulnerable. This is the sort of anti-isolationist message Rebecca Solnit shared on her Facebook page last night when she spoke of the need to pitch “a large tent.”

If there is a ‘take-away’ from the Moomin stories it is that closed system thinking cannot help us. Rather than retreat into a private world of grief or flummoxed passivity, we need to find ways of treating our vulnerability as an open window. Faced with ecological disasters, brutal wars, and the threat of destruction looming over the future of their world, the Moomins practice an insistent openness. We must too.

I’m heartened by all the positive, action-focused messaging on social media today. I know the picture book world is abuzz with good thoughts about the role of children’s books in cultivating a kinder, more compassionate world-to-come. (Solnit: “Half the five-year-olds in the USA are nonwhite; the future they make will be beautiful; we just have to hold onto what matters until they take the wheel and steer us onto a better road.”)

I have great faith in my community of co-creators. I believe wholeheartedly in the power of art to reenvision the possible. To conceive of the world “as if it were other than it is,” Amitav Ghosh reminds us, is the great project of fiction. It is also the great project of reaching toward a common world (one with proper shelter, healthcare, food security, education, and climate stabilization for all!) As writers we have the opportunity to fashion new scenarios and fresh pathways. We have the power to to enter the dark woods of a reimagined community, a community that constantly tests and reconfigures the range of ‘us’.

I’m going to keep the Moomins close at hand. I want to surround myself with stories (and movements) that model interdependence; that nurture human and non-human diversity; that foster a sense of welfare beyond biological kinship and self-interest.

“What will we do with our fear?” Where will we go? How will we enact our hope? We’re implicated in this mess differently, but we can choose to be in it, fighting and flourishing, together.