(“Snow country children going to a New Year’s event, covered in straw capes to protect them from the weather” by Hiroshi Hamaya, Niigata, Japan, 1956.)

I want to share this excellent article by Vimala Jeevanandam. It ran a few months ago in Quill and Quire (Canada’s book trade mag.) I missed it at the time and I have no idea if it gained any traction or sparked a wider conversation but I enjoyed reading it and hearing what the other authors had to say. It’s pleasantly surprising and weirdly unexpected to have a journalist take up the issue of diversity so intelligently and unapologetically (a sad commentary on the state of media and literary affairs in this country, I know.)

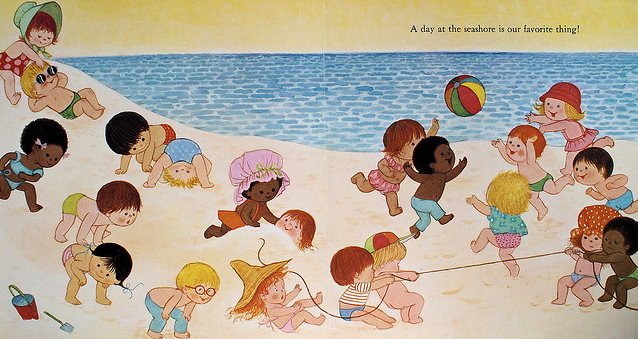

(Illustration by the trailblazing American illustrator and author Gyo Fujikawa.)

“The whole culture is telling you to hurry, while the art tells you to take your time. Always listen to the art.” —Junot Diaz

(Art by Masako Kubo and Gary Bunt.)

“Why do some people not have food?” I remember when my eldest son first asked me that. He was five years old and he was asking me to explain a confusing and sad reality. Instead of offering one of the usual bromides, I decide to share my belief that hunger in a world of surplus is unjust. “But you can change that,” I added. “How?” he asked.

When I told him he could change the state of the world, I was repeating something my great aunt Kenie, a woman I loved so dearly, once said to me when I first learned about apartheid. I came to her because I felt betrayed by this glaring evidence of adult failure. In one instant, the world went from being a place of possibility to being a place of inconceivable cruelty.

I was fortunate to have role models who showed me that when you consider something worth fighting for, it’s important to take a stand. As my great aunt put it, her hands jiggling an invisible globe: “It’s a matter of rebalancing things.” (“And for the love of God,” she likely added, peerlessly optimistic, “don’t look so glum!”)

My great aunt was a children’s story writer who introduced me to a world rarely envisioned in children’s literature. She mailed me tales full of shadows and defiant messages. She sent me my first Maurice Sendak book and introduced me to images of lurking danger, to tales of woeful but willful children.

When I was sixteen, I carried her message with me and joined a group called Youth Against Apartheid. I immersed myself in the South African expat community in Toronto, studied the history of the South African liberation movement, campaigned for sanctions and divestment, learned freedom songs and (most of) the words to the ANC anthem N’Kosi Sikeleli Africa, picked up some gumboot. I met Min Sook Lee, another YAA member, who is now a wonderful social justice filmmaker. And on Feb. 11, 1990, I watched with the world and celebrated as Mandela walked out of prison after 27 years in captivity, holding hands with his then-wife, Winnie, lifting a fist and smiling broadly. The impossible had come true and an international movement had made it happen. Four months later, I stood awestruck before the Mandelas at Queen’s Park as part of a small welcoming committee. I was there as a “youth representative.” All I remember is the dizzying and surreal feeling of hugging him as my knees buckled and Winnie caught me in her arms.

To say that the world is unremittingly bleak (that there will always be injustice) would be to turn my back on my children. To say that it is beyond hope would be to ignore how things can change; how slight, far-flung efforts can meld into a congruous movement of sorts; how people can come together and crowd out insupportable facts; how a culture of repression can be transformed into a culture of freedom.

Thank you, Madiba, for all you taught me. Rest in peace. Amandla Awethu.

(Image at top: detail of Nancy Spero’s installation “Cri du Coeur,” her last large work on paper, made after her husband’s death in 2004. Spero died in 2009 at 83.)