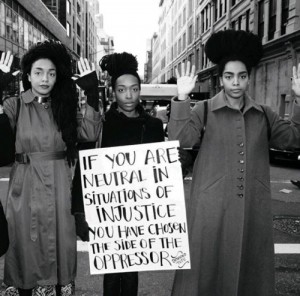

As ‘diversity’ is set to become the next big publishing phenomenon, I have been thinking increasingly about what diversity means, what it desires, what it demands. I have noticed (alongside many, many, many others), how easily the language of diversity has been superficially and cosmetically adopted, often replacing or displacing other ways of talking about social justice, power, and institutional exclusion.

I have noticed how the inclusion of certain kinds of diversity can act as a form of appeasement—forestalling often necessary conversation and, yes, conflict. (Note: we are fairly conflict-averse in the kidslit world. Every one is so damn nice! As one children’s author put it to me: “It’s a bunny eat bunny world out there.”)

I don’t know how to get at all the questions and concerns I have about the way these conversations are unfolding but I think it would be helpful to clarify what we mean when we say “diversity” because, good intentions and inclusive rhetorics aside, I don’t think we always mean the same thing. In fact, I think there are many disparate models of diversity at play in the world of picture books.

Here are a few I’ve noted:

‘Realistic’/Sociological Diversity

These books tend to focus on a community with realistic characters facing contemporary scenarios (often dealing with explicit ‘problems’ such as poverty, urban blight, migration and resettlement and often featuring descriptive language/illustration.)

Biographical/Historical Diversity

These books are what Christopher Myers calls the traditional “townships” for characters of colour. They sometimes intertwine a historical perspective with personal experience (again, they often feature descriptive language/illustration.)

Allegorical/Parable Diversity

These books tend to tackle “prejudice” by taking a disarmingly whimsical and/or symbolic approach. Animals, objects (sporks!), colours may stand in for humans in an attempt to represent difference in a non-threatening way.

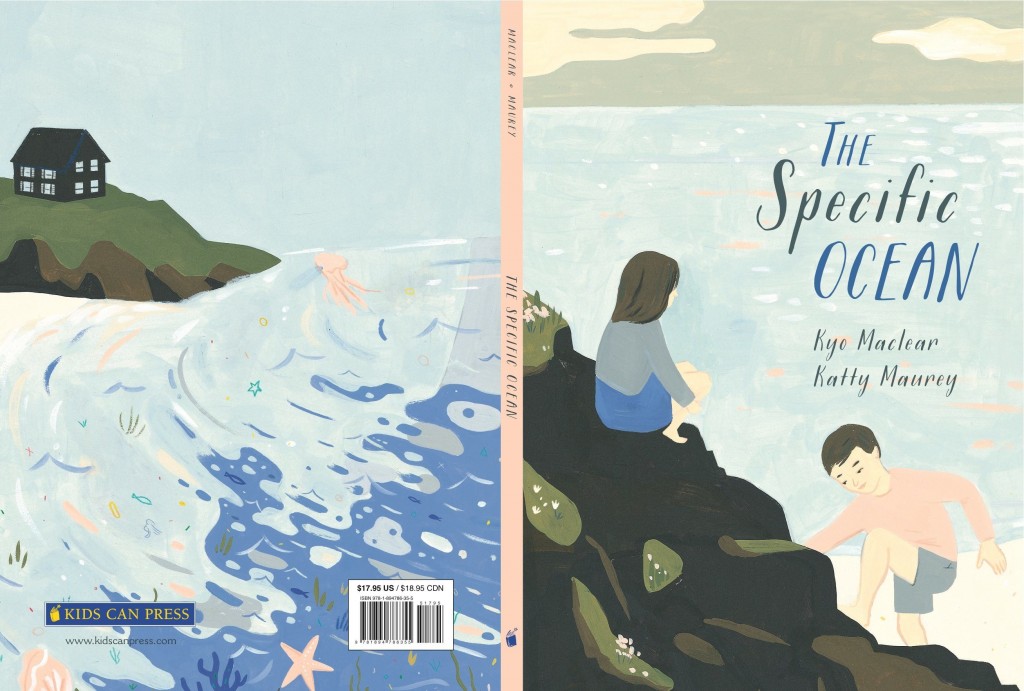

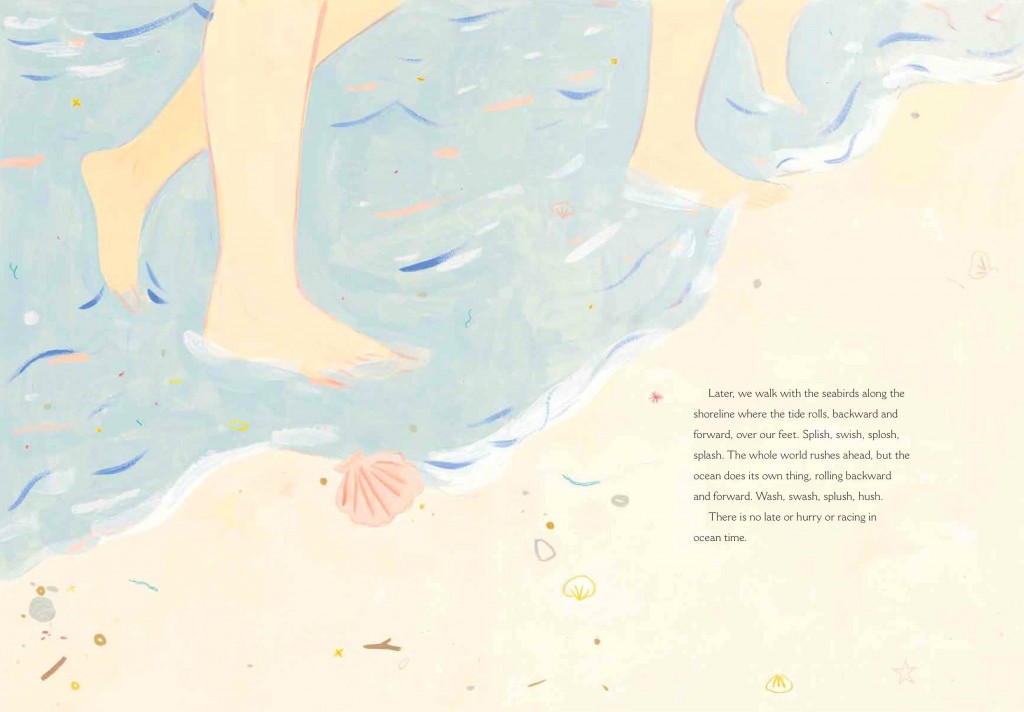

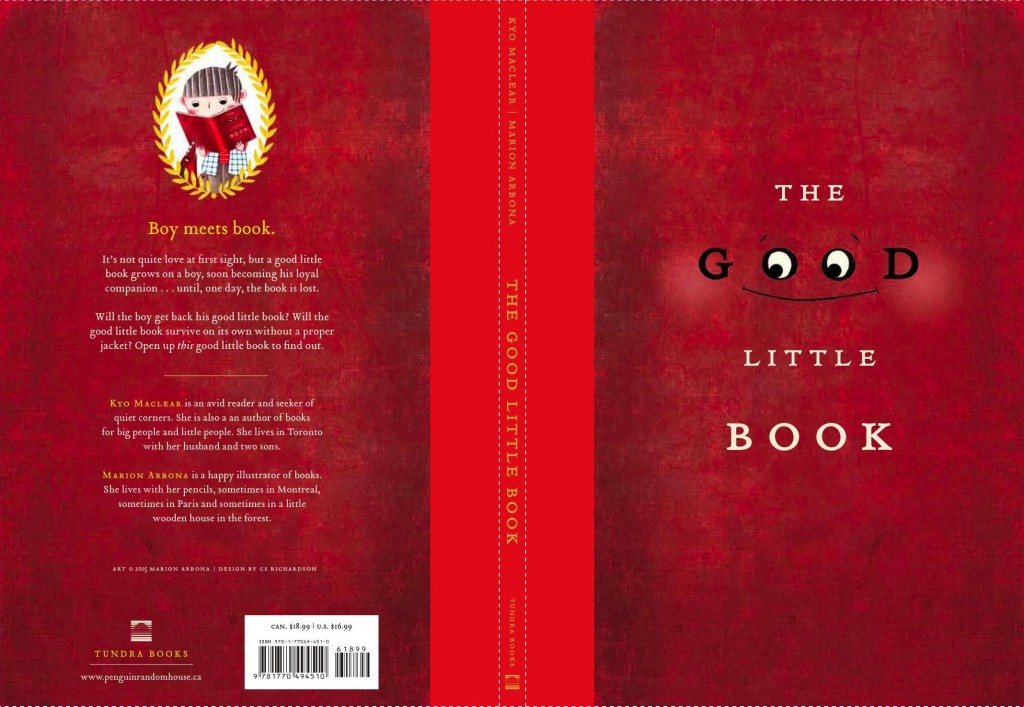

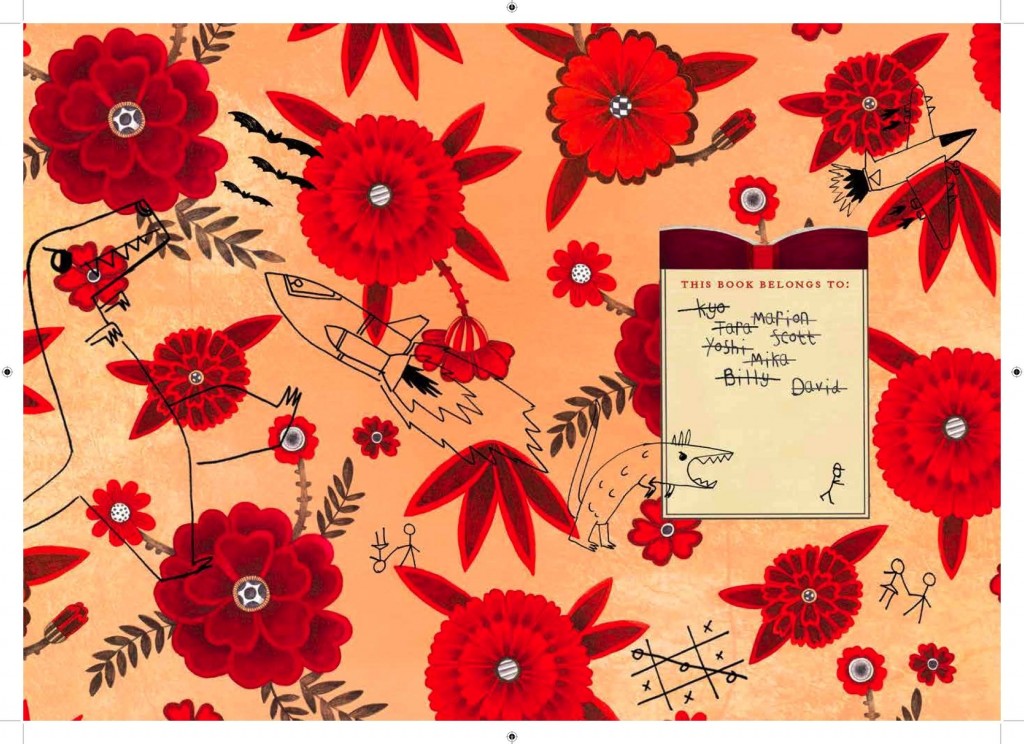

Rooted but Expressive Diversity

These books feature racially specific characters and contexts but often involve fanciful flights of adventure, imagination or personal growth (usually using expressive illustration.) Christopher Myers notes that many children “see books less as mirrors and more as maps. They are indeed searching for their place in the world, but they are also deciding where they want to go. They create, through the stories they’re given, an atlas of their world, of their relationships to others, of their possible destinations.”

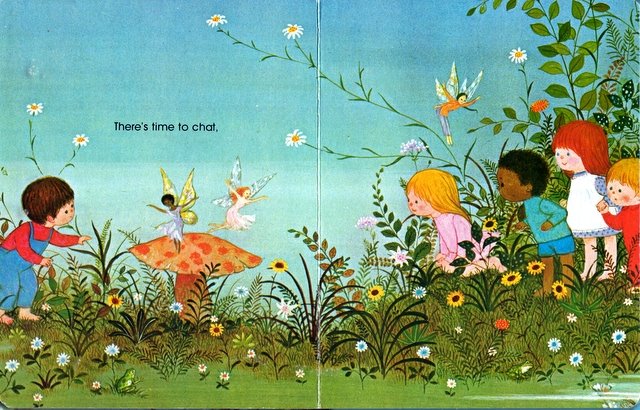

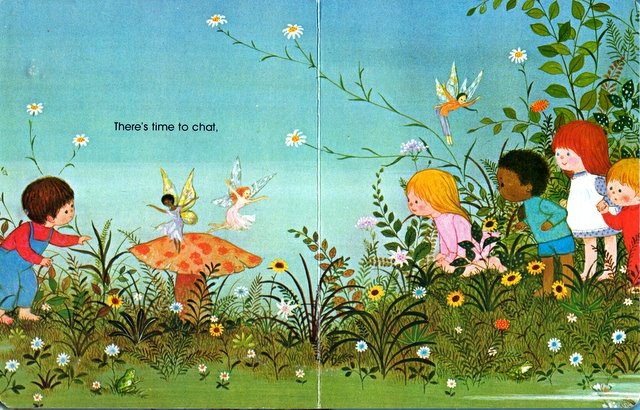

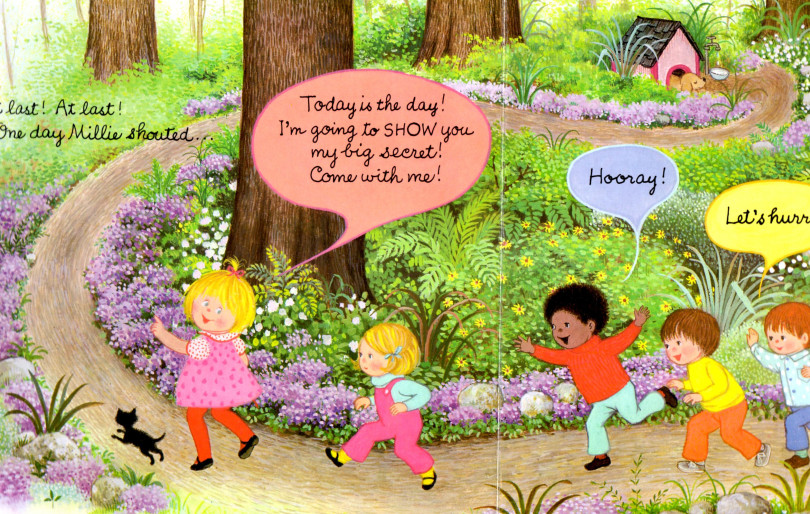

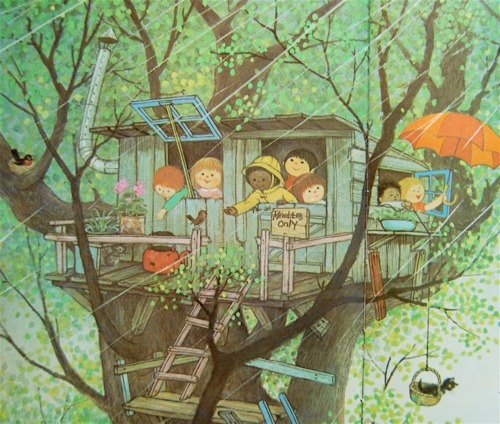

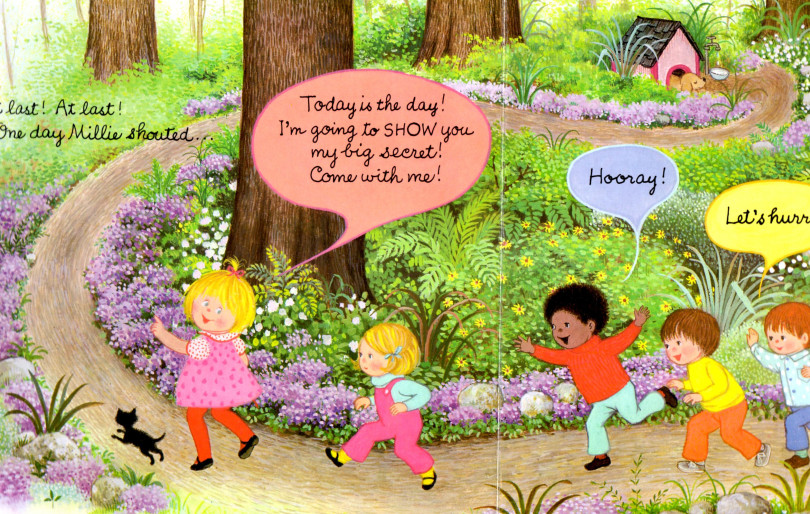

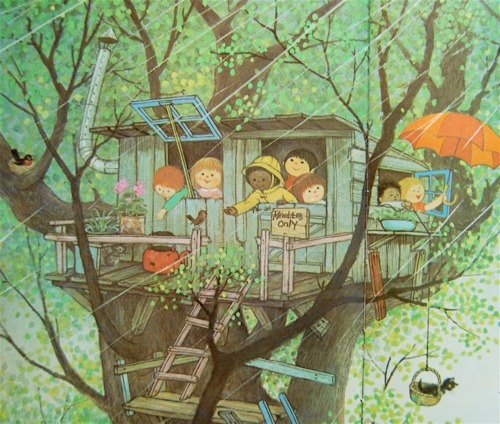

Casual Diversity

These are books in which the characters’ minority status is not central to the plot. Some call these stories “culturally neutral.” Often there is a blanding of cultural and historical specificity and a strong tendency to fall back on eternal and universal values like “using your imagination” or “loving animals.” I’ve noticed that casual diversity is a growing (and dominant?) diversity trend. (Note: this approach, while visually and even emotionally appealing, makes me nervous because it is so easy and so effacing of conflict and history. One of the challenges in the kidslit world is that liberal humanism is so entrenched, it can be difficult to challenge the “we are all the same” narrative without coming across as a complete killjoy. For writers and readers of color, there may also be a politics of gratitude at work. We are so grateful to be accepted at the proverbial literary table that we cease to question who is doing the accepting and on what terms.)

Backdrop Diversity

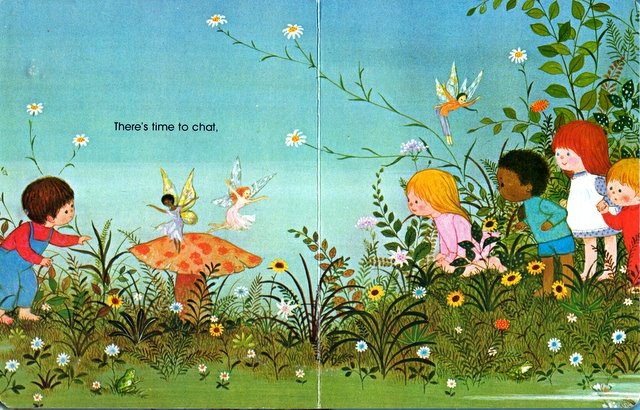

An extension of casual diversity, these books tend to feature an array of cultures/races as background characters. Again, difference is portrayed as non-threatening and universal. (I struggle with casual and backdrop diversity because I think this approach may allow for gentle, age-appropriate conversations about inclusion—providing a ‘mirror’ for younger children—but I wonder if it’s also appealing to adults who find it more sellable.)

Encyclopedic Diversity

These books tend to show a glorious array of costume, décor, landscape, homes, to represent worldliness and/or cosmopolitanism. The problem with encyclopedic diversity is that the form itself is limiting. Curt text combined with metonymic images have a tendency to become stereotypical and feel weirdly anthropological. This is generally not an approach that well-serves the historically ‘othered.’ How, after all, do we explore and address race and difference, if the race and cultural identity of characters aren’t developed? (Note: in many ways, this is a challenge intrinsic to any 200-800 word text! This is my struggle as a writer too.)

What I am proposing in all of this is that one can have a robust display of differences without at all challenging norms or structures of dominant identity.

The strategy of erasing historical and cultural specificity in favor of visual pluralism, for example, stops us at the surface of the image. It is cosmetic. Moreover, it presents difference in a palatable, eminently marketable way. (Lest we forget the lessons of 1980s Benetton-style globalization: difference is a commodity fetish.)

As writers, editors, publishers, reviewers, bloggers, teachers… as book people, I think we need to be aware of the moments when our ‘diversifying’ efforts become tokenizing, essentializing, or aestheticizing. I think we also need to be mindful of how certain characters ‘of colour’ are played off others or turned into ‘model’ picture book minorities. (i.e. Maybe it’s not enough to ‘pop an Asian character’ into your story. As Paula Young Lee recently noted: “Asians are now also 21st century versions of your ‘one Black friend,’ a kind of moral cloak protecting white people against accusations of racism.”)

In all of this I want to emphasize that inviting a critical conversation about diversity is not about calling out or shaming individual books, authors, illustrators, or publishers. It’s about the subtler, knottier work of changing institutions and attitudes that enforce dubious conventions and defaults that acquire the lustre of “tradition” or “popular taste.” It’s about ensuring that we move beyond representational inclusion towards systemic inclusion, which would include a long-term commitment to diverse writers, editors, publishers, reviewers (through mentorships, grants and paid internships.) It’s about nurturing stories that may be more specific and less broadly sellable. And it’s about respecting children and not underestimating their willingness to take on thorny, thought-provoking subjects or their openness in approaching the complicated and unfamiliar–especially if the stories are beautiful, funny, dramatic and non-medicinal!

Which brings me to another model of diversity, what some have called:

Critical Diversity

These books are not about creating symbols or markers out of difference. They are not about finding models of successful or paradigmatic blackness (or indigenousness, Asianness, Hispanicness, etc.) that can (in the words of Ta-Nehisi Coates) be “singled out, made examples of, transfigured into parables of diversity.” Critical diversity allows us to see “how broad the black normal is” (Coates). Critical diversity moves beyond superficial inclusion to highlights differences within communities, accounting for class position, disability, gender, religion, etc. In scholar Rinaldo Walcott‘s words, if we are to get at “the depth and texture of how blackness is experienced and lived out in both its extra and intra-black differences” it cannot “only be framed and understood in relationship to race and racism. Thus critical diversity seeks to not just populate our various arenas with one-dimensional encounters. It seeks to provide encounters that strike deeply at the core of what it means to be human.”

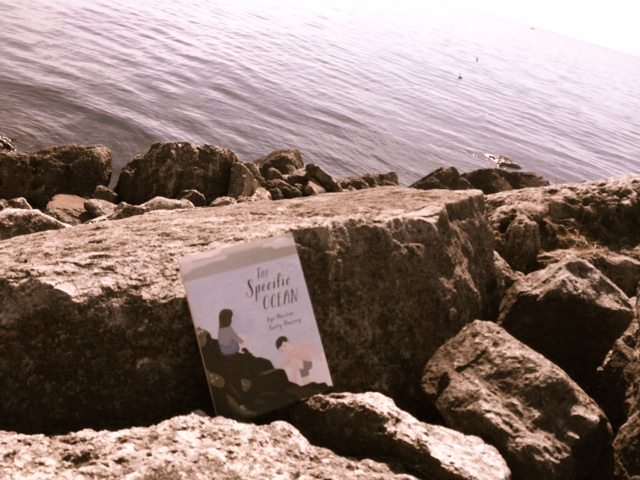

The current dialogue about diversity is a wonderful and welcome starting point and there are so many thoughtful and inspiring initiatives, including these recent ones by Simon and Schuster and the trailblazing Groundwood Books .

My final point, if I have one, is that perhaps we need to be both fast and slow in our speed of change, both expeditious yet reflective as we move forward. I do feel that in a scramble to fill the vacuum, we may rush towards a ‘panicked diversity’ (again, ‘toss an Asian character in there and be done with it’). Let’s remember that this is a generations’ old conversation. Let’s make this conversation lasting and systemically meaningful so that it continues well past the current marketing and media moment.

Thank you. xx

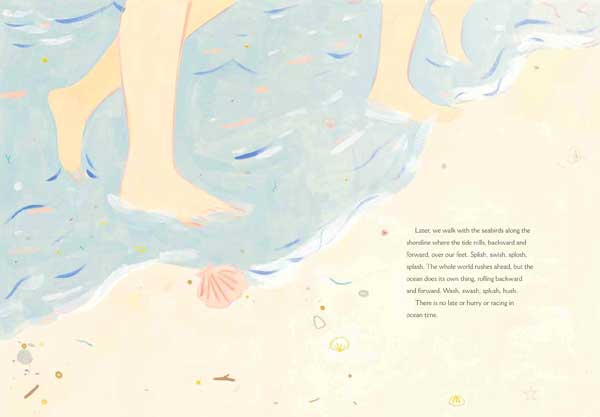

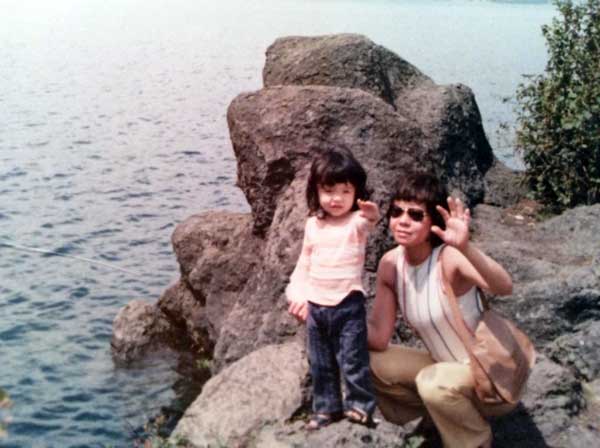

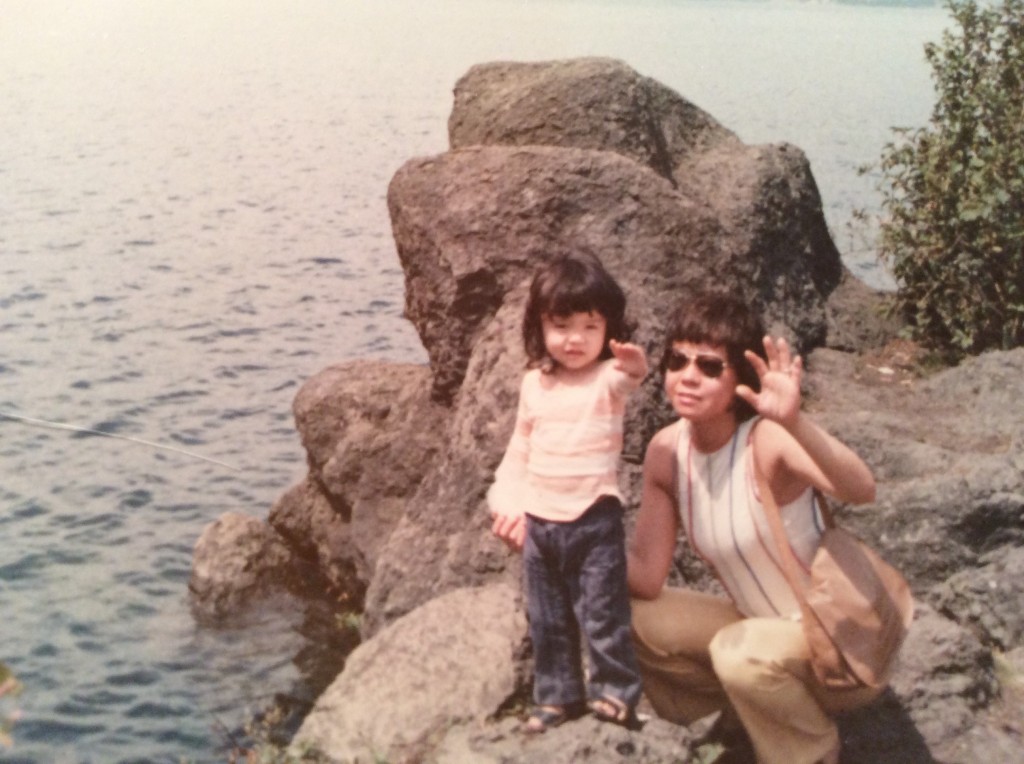

(With special thanks to Professor Cheryl Cowdy at York University who invited me to speak to her undergraduate class today, thus inciting many of the thoughts shared here. Note: all illustrations are by Gyo Fujikawa and date back to the 1960s.)