Our family has been having a love affair with the absurd. Monty Python. Yellow Submarine. Fluxus. The Marx Brothers. (Note my recent posts on absurdity.) What I like about the absurd is how it thumbs its nose at what André Breton once called our “reign of logic.” In fact, it subverts the very idea that being realistic is a desirable way of being in the world. Instead, the absurd unfurls our imaginations, responds to the status quo with a gag or poetry. It puts a flower inside the barrel of a gun, eats an old leather boot for dinner.

In my opinion, no one uses the absurd as well as George Saunders. Saunders writes about strange characters and strange things in a hilariously deadpan tone. As a satirist, he inflates reality (whether is be consumerism or corporate culture) to such bizarre proportions that he allows us to see things better.

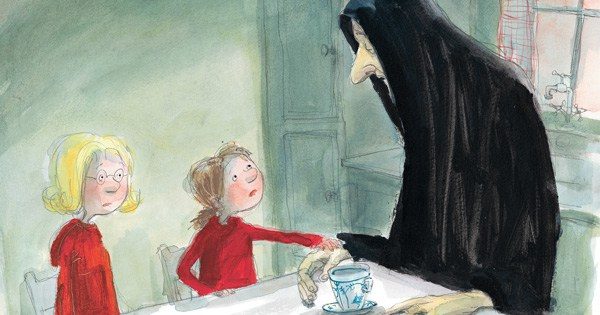

His brilliant book, The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip, is a fable for children or a fairy tale for grown-ups. It is wonderfully and weirdly illustrated by the ever-spectacular Lane Smith.

A quick summary: Three families live in the tiny seaside village of Frip—the Romos, the Ronsens, and a little girl named Capable and her widower father who is obsessed with the past. The townspeople of Frip make their living raising goats, but they must fight off a daily scourge of gappers. (In case you were wondering, gappers are baseball-sized, burr-shaped orange creatures that creep up out of the sea and fasten themselves to goats and stop them from producing milk.) Since Frip survives by selling goat milk, the children must brush gappers off the herd eight times daily and dump them into the ocean. When the gappers target Capable’s goats, the Romos and the Ronsens turn their backs on the gapper-ridden Capable.

As a modern morality tale, the story weaves in lessons about how the misfortunate are disparaged, how the rich make excuses for why the poor are poor and why they can’t help, how some girls try to make themselves look pretty by standing very still.

(Imagine if 99% of the population was dealing with a scourge of gappers that caused their share of the economy to dry up. What would the 1% do? Surely it would not greet the 99% with a cold shoulder!)

In Saunders’ story, the plot hinges on whether the neighboring families will overcome their own selfishness, hypocrisy and self-righteousness. Do they? Well I don’t want to spoil the story, but I can tell you this much: everything ends unusually well.

p.s. This week I also read and loved My Name is Mina (prequel to Skellig.) When I finished it, I wanted to thank David Almond personally for the believable and tender way he expresses things. And, yes, Almond definitely has his surreal moments.