On the eve of my marriage, in August 1998, my father gave me a beautiful lacquer box with a black and white photo inside. It showed my father from behind peering out over a lunar landscape. Written on the back were the words:

This is a very historic photo of a time of horror and happiness. In September 1969 I traveled from Hanoi to the border with the South — the first television correspondent to do so. What I saw no one in the West at first believed, countryside bombed so totally that it looked like the craters of the Moon. When I returned to Hanoi (traveling at night to hide from the bombing), I vowed I’d do a television history of Vietnam some day to “repair” the damage. That same day in Hanoi I received wonderful news that forever altered my life: a telegram from Mummy saying you were on your way!

My husband thought it was a lovely but strange wedding gift. On the one hand, there was the photo — black marks of bomb impacts on the ground. On the other hand, there was the refined lacquer container, subtly inlaid with mother of pearl, a reminder of my father’s simple and exquisite taste. Devastation and beauty. Horror and happiness. After years of observing my father, however, I didn’t see it as strange at all. Intense maybe, but not — in the out-of-character sort of way — strange.

In the months and years after our wedding, I kept going back to that box. It seemed, in that manner of certain keepsakes, to offer some basic truth: life is a paradox, a combination of contrasting elements.

Do we not all have a box somewhere? The box that goes by different names — identity, the past, childhood — but which speaks to our emotional inheritance?

(Click here to read the full blog post.)

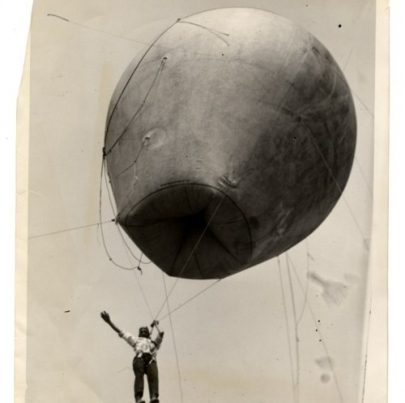

Image: Garden at Westminster Cathedral, London, created from bomb crater, 1942.