As a child, I remember my father whirling around the world. I seldom knew where he was going. But I knew the news would take him there. I also knew that of all the countries he visited, it was Vietnam that stole his heart. He made his first trip there in 1959, more than a decade before I was born, and continued to revisit on and off over twenty years. He was the first Western television reporter to show the bomb damage to civilian areas caused by American raids (“a countryside bombed so totally that it looked like the craters of the Moon”). In 1969, he broke the news of Ho Chi Minh’s death to the world and was the only reporter invited to attend the funeral. A year later he was the first reporter to interview American Prisoners of War. “In prison cells replete with Christmas trees for the extraordinary occasion, for the first time a few of the POWs are allowed to tell of their conditions and their sentiments.” These interviews caused a stir in the United States. In 1972, he saw the first US air strike on Hanoi. In the late 1970s, he obtained exclusive access to film from Hanoi’s military archives and began work on a comprehensive TV documentary on the war in Vietnam. Dien Bien Phu, My Lai, Khe Sanh… I grew up with the Vietnam War scrolling in the background. I have often wondered what it was like for other children of war reporters.

As a war reporter and later a documentary filmmaker, my father made a life of doing what most people avoid—he rushed towards disaster. He faced forward when others would have looked or run away. For reasons I never fully understood, war beckoned my father. Perhaps the brutal act of fighting was a clearcut expression of the drama of living. Or maybe it allowed him to step into a meaningful narrative. War is a good story. Someone is always losing something.

A few months ago, I clipped an article about a documentary called Under Fire: Journalists in Combat. When the filmmaker, Martyn Burke, was asked why he felt his subjects felt compelled to keep putting themselves in harm’s way, he replied that he didn’t know: “none of them ever gave me a real answer that I could hold onto…There are all the answers that are true—that it’s important, that it brings us news from places we need to know about, that there’s an adrenalin high and more—but there’s this unknowable personal component that’s still floating around in the ether and has not been bottled and examined, and may never be.”

It’s this “unknowable personal component” that continues to fascinate me when I meet people who put themselves in the line of fire. It’s the elusive backstory and motivation, not yet “bottled and examined.” In the end, I think it’s our fictions (the stories we dream up) that allow us to we get closest to these mysteries.

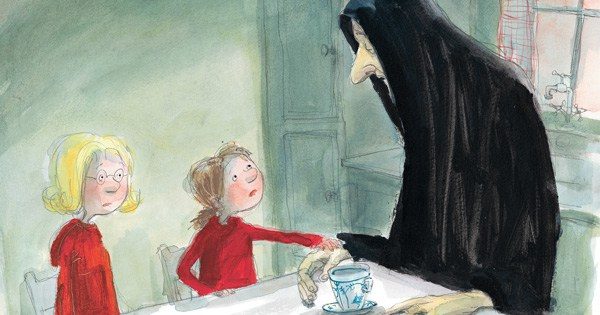

(My drawings of men and women who reported from Vietnam.)