Yesterday I attended a quiet memorial for a beloved graduate school professor—a wonderful and serious scholar named Roger Simon—who passed away last September after a difficult illness. It was both moving and strange to be in a room full of former classmates and colleagues, many of whom continue to work within the university. I don’t mean to slag academia (“Some of my best friends are…” and at the level of influence I still consider myself part of that extended family) but it did strike me at several moments how decorously cerebral and painfully restrained the whole event seemed. It’s not that I expected outpourings of grief or the rending of garments—my former professor (a man whose very work addressed cliches of mourning and cheap appeals to sentimentality) would have shuddered at the prospect—but, still, I wanted something more.*

I have many fond memories of grad school. Nothing surpasses that feeling of being very intellectually AWAKE in a community of other very AWAKE people. But the entire time I was there, I always felt that something was missing. Some pulse. Some mystery. (The words “I feel” may have limits but to not use them at all is also limiting.) Of all the courses I took, it seems somehow fitting that the one that stays with me most vividly was a novel-reading class. It was led by a brilliant visiting scholar-writer who used Edward Said’s Culture and Imperialism as a starting point for reading “contrapuntally.” And, so, we read Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea in counterpoint to Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, then Maryse Conde’s I Tituba, Black Witch of Salem in counterpoint to Arthur Miller’s The Crucible.

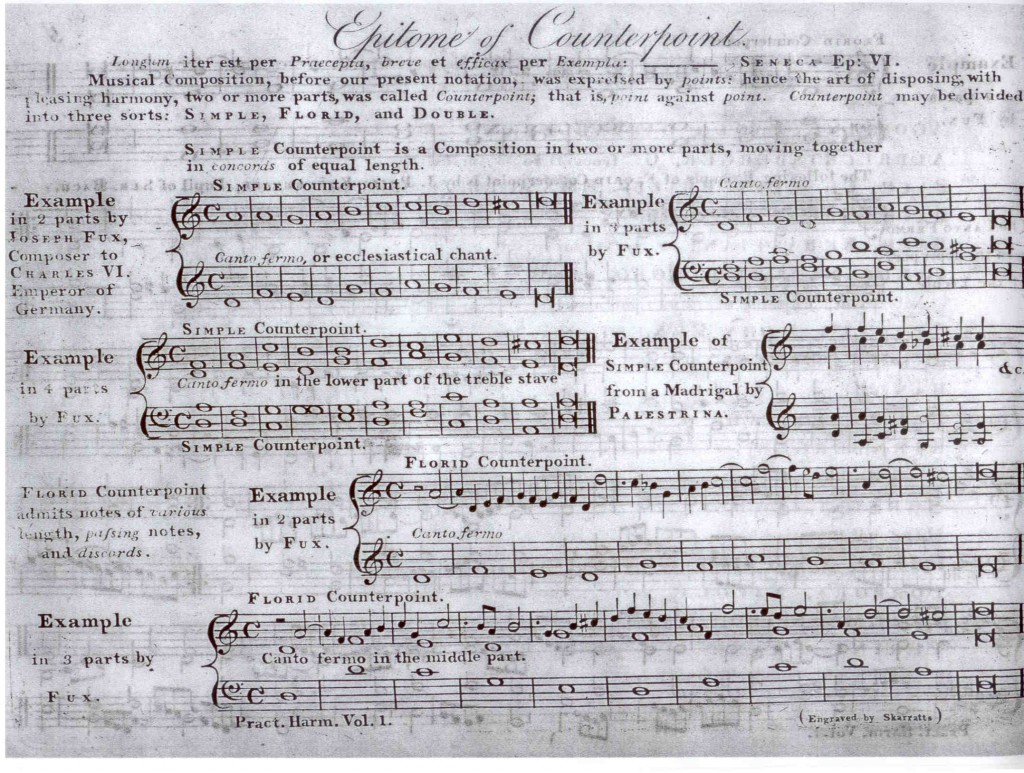

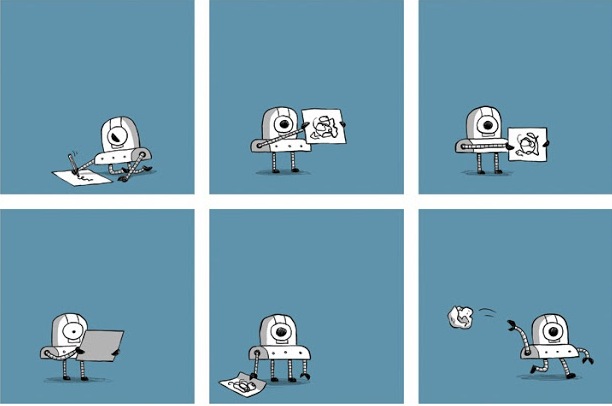

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between voices that are harmonically interdependent, but independent in contour and rhythm. Similarly, reading in counterpoint is not a matter of antagonism but of polyphony—recognizing how different voices are attuned to each other. It’s a way to see how one storyline can reveal the shadow of another and it’s a way of taking the parts that have been separated and integrating them back into our awareness and hearts.

Edward Said’s own illness became the sad counterpoint to his writing in his final years. In his last book, completed posthumously by his close friends, he poignantly noted that he was “always interested in what gets left out”…the counterpoint to any moment.

Maybe what I wanted yesterday was more counterpoint. More music. More art. A different contour and rhythm. Something to ambush our habits of separating intellect from emotion. Something to honor our fumbling, ineloquent acts of remembering.

*There is a beautiful poem written by Mahmoud Darwish for Edward Said which addresses the difficulty of easy elegy: “And nostalgia for yesterday? A sentiment not fit for an intellectual, unless…”

(Image: Clementi’s ‘Epitome of Counterpoint’ from the 1st volume of his Selection of Practical Harmony, original 1801 edition.)